The BBC’s latest crisis began over a few seconds of video. Selectively edited by the BBC, a Panorama documentary broadcast in October 2024 spliced together two parts of a speech by Donald Trump on 6 January 2021, making it appear that he had urged his supporters to “fight like hell” and march with him to the Capitol.

He said no such thing – certainly not as the BBC portrayed it in the Panorama episode.

The revelation, exposed by The Telegraph in early November and confirmed by a BBC whistle-blower, unleashed a storm that few inside Broadcasting House seemed prepared for.

On 9 November, Director-General Tim Davie and Head of News Deborah Turness both resigned. Trump threatened to sue the BBC for $1 billion, claiming deliberate deception. The BBC’s chairman, Samir Shah, apologised for an “error of judgment” and promised to restore public trust.

Whether Trump’s lawsuit succeeds hardly matters. Legal experts note that his chances are slim: the UK’s 12-month defamation window expired two weeks earlier, and BBC iPlayer isn’t even available in the United States.

What matters far more is the institutional damage to trust, credibility, and the BBC’s sense of purpose.

A pattern of failure

As The Economist observed, this is not the first time the BBC has been engulfed by scandal – or even by one of its own making. The Panorama debacle followed Ofcom’s censure over a Gaza documentary, and earlier, the BBC’s broadcast of a Glastonbury performance that included anti-Israeli chants in breach of editorial guidelines.

These are not isolated lapses. They are symptoms of a deeper problem: a leadership culture that confuses process with principle. Time and again, when faced with criticism, the corporation hunkers down, issues holding statements, and waits for the outrage to pass. As Mark Borkowski wrote on LinkedIn, the BBC exemplifies “the pathology of big institutions – managing optics instead of outcomes.”

A political and existential moment

This crisis could hardly have come at a worse time. As POLITICO reports, the BBC is about to enter fraught negotiations over its Royal Charter and funding model, which expire in 2027. That process will determine whether Britain continues to have a publicly funded broadcaster in anything like its current form.

The political stakes are immense. Reform UK leader Nigel Farage called the affair “the final straw,” describing the BBC as culturally broken and demanding an end to the licence fee. Conservative leader Kemi Badenoch echoed that view, arguing that funding should be contingent on impartiality.

Even Labour's Culture Secretary Lisa Nandy, while defending the BBC’s public value, has said she is thinking “quite radically” about alternatives to the current model. In a debate in the House of Commons on 11 November, she described the BBC as "essential to this country."

The BBC’s defenders insist that its independence must remain sacrosanct. Former Conservative culture secretary John Whittingdale warned against conflating funding with editorial integrity. Yet the two are already entwined. The licence fee itself – long seen as a guarantee of independence – is increasingly viewed as a lever of control, a mechanism by which governments and populists alike can threaten the broadcaster’s existence.

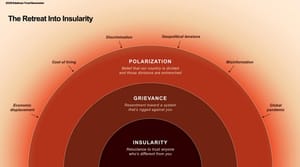

Built for reason, trapped in emotion

Borkowski’s phrase – that the BBC was “built for the age of reason and now finds itself trapped in an age of emotional velocity” – captures the heart of the problem. The corporation’s governance model, devised in a slower, more deferential time, no longer fits the pace or psychology of today’s public sphere.

In an age of social outrage and digital dogfights, bureaucratic restraint reads as aloofness; procedural caution looks like evasion. The BBC’s instinct to retreat into process – to review, to consult, to apologise only when cornered – is precisely what erodes public trust.

Katie Razzall, the BBC’s culture and media editor, put it bluntly: the apology came too late, the response too slow, and the tone too defensive. By the time the chairman spoke publicly, the narrative had already hardened – one of bias, arrogance, and denial.

The cultural diagnosis is clear – now comes the structural one.

Leadership or design?

The reflexive solution will be to appoint another Director-General and move on. Yet the BBC has had five Directors-General in two decades, each departing amid scandal or controversy. Replacing the person at the top is not fixing the structure beneath.

This is no longer a leadership issue alone; it is an architectural one. The BBC’s governance, its lines of accountability, and its funding model all belong to another era. If true independence is to mean anything, the corporation must be re-engineered – with a public trust model, for example, separating oversight entirely from government. The licence fee could evolve into a "citizens’ contribution," transparently allocated through an independent body rather than the Treasury.

The real test

The BBC remains one of Britain’s greatest institutions, admired worldwide for its journalism, storytelling, and reach. But institutions endure only when they evolve, when they remember that trust, once lost, can’t be rebuilt through process alone.

Real leadership now means more than steadying the ship; it means rebuilding it. Not to appease political critics, but to protect the BBC’s founding purpose – to inform, educate, and yes, sometimes enrage – in a world that has moved on from the certainties of John Reith’s day.

Independence is not simply a principle to defend when under attack. It’s a system that must be designed, protected, and renewed. Until that happens, the BBC will keep mistaking motion for progress while the ground shifts beneath it.