The news announced last week that OpenAI plans to introduce advertising into ChatGPT should surprise no one. It may still unsettle some users, but commercially, I've always believed it was a matter of when, not if.

According to a Financial Times report, OpenAI will begin testing ads in the US in a few weeks' time on the free version of ChatGPT and its low-cost ChatGPT Go tier. Paid subscriptions – such as to ChatGPT Plus, the one I subscribe to – will remain ad-free.

OpenAI reportedly expects advertising to generate “low billions” of dollars this year, helping fund the extraordinary compute costs required to keep the system running and competitive.

At the same time, OpenAI has published an explanation of how it intends to introduce advertising and the principles it says will govern that move. The clarity of that post is welcome. But clarity alone will not resolve the deeper issue this change brings into focus.

Why advertising was always going to happen

ChatGPT has reached a global scale at a remarkable speed. Hundreds of millions of people now use it regularly, many for thoughtful, personal, and professionally significant tasks.

But scale comes with cost. Training and running large language models require vast, growing amounts of compute (jargon for 'computer power'). Subscriptions alone, even with millions of paying users, are unlikely to fund that ambition indefinitely.

Advertising has long underpinned the economics of free or low-cost access on the internet. Search engines, social platforms, and content sites all travelled this road. In that sense, OpenAI’s move is entirely conventional.

The difference is not the business model. It is the relationship users have with the product.

What OpenAI says it will do – and not do

In its own blog post, OpenAI lays out a set of principles designed to reassure users as advertising is introduced.

In summary, the company says:

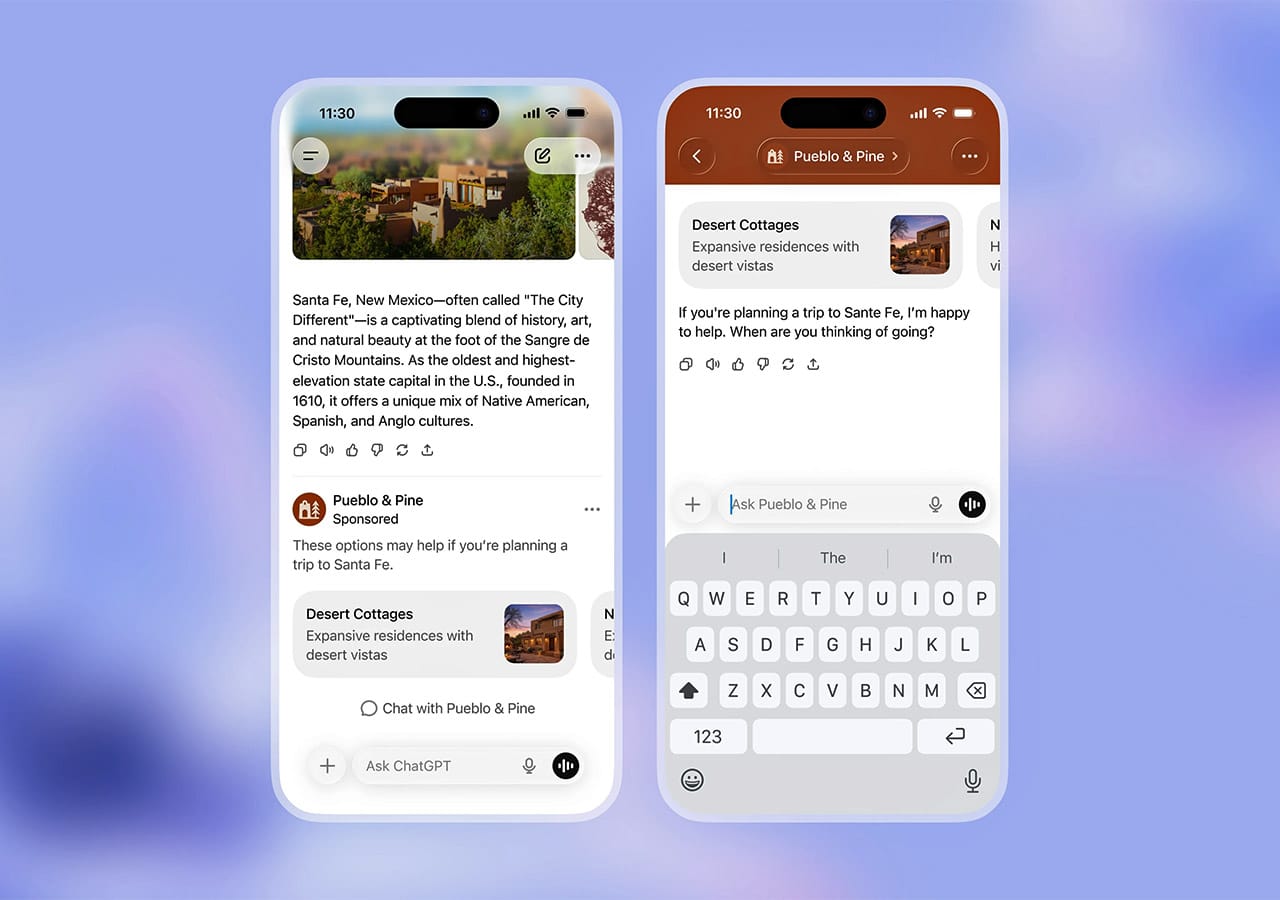

- Ads will be clearly labelled and visually separated from ChatGPT’s answers.

- Advertising will not influence the content of responses.

- Conversations will not be shared with advertisers, and user data will not be sold.

- Users will have control over personalisation and can turn it off.

- Ads will not appear for under-18s or alongside sensitive topics such as health, mental health, or politics.

- There will always be a paid, ad-free option.

OpenAI also states explicitly that it does not optimise for time spent in ChatGPT, and that user trust and experience take precedence over revenue.

But commitments are only the starting point.

ChatGPT is not search or social – and that matters

People do not use ChatGPT in the same way they use a search engine or scroll a social feed.

They think with it. They draft with it. They explore half-formed ideas, test language, ask questions they might not ask elsewhere. The interface feels conversational and, to many users, implicitly private.

That perception – whether technically accurate or not – creates a much higher bar for trust.

Advertising in search sits alongside links. Advertising in social feeds sits among posts. Advertising in a conversational assistant feels closer to advice, reflection, or collaboration.

This is why the stakes are different.

Data privacy – where trust will be tested first

OpenAI is clear that advertisers will not have access to user conversations and that data will not be sold. That distinction is important.

However, ads will be shown when they are “relevant” to the current conversation. That immediately raises understandable questions for users:

- What aspects of a conversation are analysed to determine relevance?

- How is inference separated from disclosure?

- How does this interact with ChatGPT’s growing use of memory and personalisation?

None of these questions implies bad faith. But they do highlight how easily confidence can be shaken if users feel the boundaries are unclear or shifting.

The Wall Street Journal reports that OpenAI CEO Sam Altman previously warned that introducing ads into ChatGPT could erode trust with users if they believe the chatbot’s answers are being influenced by advertisers.

OpenAI states unequivocally that advertising will not influence ChatGPT’s answers. Ads will be separate, clearly labelled, and subordinate to the response.

Even so, users may reasonably ask a subtler question: not whether answers change, but whether their interpretation does.

When a sponsored product or service appears beneath an answer, especially in a conversational context, some users will inevitably wonder about influence, even if none exists. That is not a technical problem – it is a human one.

Trust is fragile. Once users begin second-guessing motivation, it is difficult to rebuild confidence, however robust the underlying systems may be.

Transparency and control help – but they are not enough

There is much to commend in OpenAI’s approach so far. Publishing principles in advance, offering clear controls, excluding sensitive categories, and maintaining ad-free paid tiers all signal seriousness.

But transparency statements do not, on their own, create trust. Trust is earned over time through consistent behaviour, clear explanations, and credible responses when concerns arise.

The real test will not be this announcement. It will be how OpenAI behaves six months, a year, and several product cycles from now.

Why this matters for communicators

This shift is not just relevant to OpenAI users. It matters to anyone involved in communication, reputation, or organisational trust.

AI tools are becoming part of the information environment itself, not just another channel. How they are funded, governed, and explained will increasingly shape public confidence.

Communicators will need to help organisations answer questions such as:

- Can we trust AI-assisted outputs?

- How is data handled and protected?

- What commercial incentives sit behind the tools we use?

These are not abstract concerns. They are becoming everyday questions.

While advertising in ChatGPT was inevitable, the careful way OpenAI is approaching it suggests the company understands what is at stake.

ChatGPT works because people trust it. Advertising will only work if that trust survives contact with reality.

And that is a test no policy document can pass on its own. This is one for the humans.