As communicators, we pride ourselves on crafting messages that build trust, shape reputation, and connect with audiences. Yet in a digital world where content is endlessly copied and reshaped, there is a new and unsettling risk: your own message can be taken from you, twisted, and used against you.

An academic study, published in the Journal of Communication Management on 19 September, gives this phenomenon a name – communication hijacking – and it is one of the more sobering challenges now facing our profession.

The researchers explain that hijacking is not simply someone disagreeing with you or parodying your work. It is a hostile takeover of communication that follows a clear pattern:

- First, it happens without the organisation’s consent or control.

- Second, it involves seizing something that already exists – a campaign slogan, a hashtag, a trusted logo – and presenting it as if it were still authentic.

- And third, it flips the meaning, reshaping that element to say the opposite of what it was intended to say.

The more forceful each of these elements is, the more destructive the hijack. They describe this relationship in what they call the Communication Hijacking Triad.

Communication Weaponised

You may recognise or see a parallel with brandjacking, a term that has been around since the early 2000s to describe how brands can be impersonated or mocked online. Fake social media accounts that imitate brands, or activists repurposing logos to criticise corporate behaviour, are familiar examples.

But communication hijacking is far more serious. It doesn’t just lampoon or exploit a brand identity – it seizes entire campaigns or institutional messages and flips them to say the opposite of what was intended. In doing so, it undermines not only reputation but also public trust, social cohesion, and legitimacy itself.

What this looks like in practice is both revealing and unsettling.

The researchers illustrate this by example, citing what happened in Finland, where a pro-Kremlin group set up a so-called “Hybrid Centre,” a near-identical copy of the European Union’s Hybrid Centre of Excellence, with the clear intent of giving its own propaganda a veneer of credibility.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Finnish government’s carefully crafted “Five Tips” health campaign was reworked and republished as the “People’s Five Tips,” spreading anti-vaccine narratives that directly undermined public health. And in another case, an anti-vaccine movement co-opted the reputation of Save the Children by launching “Let’s Save the Children,” creating immediate confusion about what – and who – the trusted charity actually stood for.

Of course, hijacking is not unique to Finland or any other single country. Globally, conspiracy theorists have exploited the hashtag #SaveTheChildren, particularly in the United States, twisting the name of the respected NGO into a vehicle for spreading QAnon-related narratives.

This phenomenon, documented by the Media Manipulation Casebook, illustrates the broader vulnerability of trusted organisations to hijacking on a worldwide scale.

Investing in Resilience

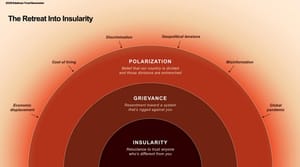

These are not minor irritations. They show how quickly reputational assets can be weaponised, how easily the public can be confused, and how fragile legitimacy becomes when the lines between real and fake blur.

What begins as a clever piece of mimicry can, in the space of hours, erode years of careful relationship-building. The rise of AI-driven tools, the viral nature of social platforms, and the rapid speed at which content can be replicated all make this threat far more challenging to contain.

So what can communicators do? The Finnish study suggests some practical answers, but I think it starts with resilience.

The clearer and more consistent our voice, the easier it is for people to recognise when an imitation is false. The stronger our reputation for openness and honesty, the harder it is for a fake to gain traction. Protecting trademarks, domains, and visual identities matter, but so does the less tangible work of being a communicator people trust instinctively. Preparation also plays a role.

If hijacking is added to crisis communication planning, then organisations will be better placed to spot the early signs and respond before the damage spreads. And when it does happen, speed is critical. Counter the false narrative quickly, explain what is happening, and stay close to stakeholders who might otherwise be misled.

For communicators, the lesson is clear: we no longer fully control our narratives, and others are ready to seize them. However, by understanding the dynamics of the hijacking triad, anticipating how it could unfold, and investing in resilience, we can mitigate its impact.

That is the task ahead – not only to tell our story well, but also to protect it when others try to rewrite it for their own ends.

Additional Reading:

- The full academic research report: "Communication hijacking: strategic communication gone dark" (PDF) by Miriam Hautala and Vilma Luoma-aho, School of Business and Economics, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, Finland; and Jason C. Brown, Army Cyber Institute, West Point, New York, USA.