When the White House opens its doors to TikTokers and podcasters in place of seasoned political reporters, it signals more than just a change in press strategy – it marks a fundamental shift in how governments see the role of media.

During 2025, President Trump’s administration has given social media “newsfluencers” – online personalities with large followings – privileged access to briefings (such as this one on 7 July) and even seats in the once-sacrosanct White House press pool. The move reflects the reality that millions of Americans now turn to influencers, not newspapers or broadcasters, for their daily news.

But it also raises uncomfortable questions about accountability, the spread of misinformation, and the health of democracy itself.

This American experiment invites a bigger question: could it happen here? Could UK or European leaders, faced with declining trust in traditional media, turn to influencers as their main conduit to the public?

Some would argue the signs are already there – from politicians bypassing journalists with slick Facebook videos, to the growing reach of partisan YouTube channels and TikTok accounts shaping political opinion among younger voters.

For communicators, this is not just a curiosity from across the Atlantic. It is a glimpse of a future where influencers and institutions collide, and where choices about who speaks for authority – and who holds authority to account – become far less clear.

The American Experiment

The Press Gazette recently reported how the Trump White House has restructured access to the presidency. Instead of leaving it to the long-established White House Correspondents’ Association, the administration has taken direct control of the press pool for the first time in a century.

Into that space, it has invited “new media”: podcasters, TikTok personalities, and self-styled citizen journalists.

These “newsfluencers” now enjoy briefing rooms, rotating seats, and even the first questions at press conferences. Unsurprisingly, many come from pro-Trump circles. Their questions typically lean towards praise rather than scrutiny, and sometimes stray into conspiracy theory.

The influencers themselves benefit from unprecedented legitimacy – the White House backdrop adds weight to their brand – while the administration gets a sympathetic platform to amplify its message.

Critics see this as a threat to democratic accountability. If the toughest questions are pushed aside in favour of easy soundbites, the ability of the press to hold power to account is diminished. And with one in five Americans now reporting they regularly get their news from influencers, the stakes are high.

Why This Matters Beyond the US

The US often sets the tone for how politics and media evolve globally. Think of campaign advertising, data-driven voter targeting, or the rise of 24-hour news channels – all of which found their way into UK and European politics. The embrace of newsfluencers may well follow the same path.

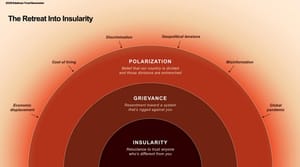

The underlying drivers are not uniquely American: declining trust in mainstream media, fragmented audiences, and the dominance of social platforms in news consumption. In that context, the logic of turning to influencers – with their reach, relatability, and loyal audiences – becomes compelling to politicians everywhere.

Could It Happen in the UK?

In July 2025, No 10 Downing Street hosted its first reception for social media creators, inviting around 70-90 influencers with a combined reach across social networks in the hundreds of millions. The event included panels on working with government and briefings alongside traditional media – a clear sign that the shift has already begun.

A few other examples of what we're already seeing:

- Boris Johnson’s “People’s PMQs” on Facebook Live a few years ago bypassed the press to deliver direct-to-camera answers.

- Nigel Farage has built a formidable following not only through broadcast outlets like GB News but also through online content designed for sharing.

- Political YouTubers and TikTokers already command significant attention among younger demographics, often shaping perceptions well before traditional outlets catch up.

The UK retains a strong political press culture, anchored by institutions like the BBC and the lobby system at Westminster. But declining trust in those institutions, combined with rising digital populism, creates conditions in which a British version of the newsfluencer phenomenon could emerge more formally.

The European Picture

Across Europe, the picture is mixed. Some countries – such as Hungary, Italy, and Poland – have already seen populist leaders blur lines between independent journalism and state-friendly media. Giving formal access to influencers in political spaces might not be a giant leap.

Meanwhile, TikTok and Instagram have become the dominant sources of political content for young Europeans – 42 % of people aged 16-30 rely on them as their primary news sources, according to recent data. In effect, influencers already serve as an unofficial press corps, and the move toward formal recognition – such as press briefing access – would hardly be surprising.

By contrast, EU institutions have been more cautious.

While the European Commission has invested in outreach – such as the Influencer Legal Hub, which guides content creators on EU regulations and advertising rules – there’s been no shift toward giving influencers formal access akin to journalists or briefings.

That said, the Council of the European Union has already signalled a changing landscape. In May 2024, it adopted conclusions encouraging member states and the Commission to support influencers responsibly – highlighting media literacy, ethical guidelines, and better engagement frameworks.

Looking ahead, the European Parliament elections in 2029 could test this dynamic further. With influencers commanding attention across the continent, there may be growing pressure on EU institutions to rethink their current gatekeeping role – and perhaps formalise influencer engagement in future communication strategies.

Implications for Communicators

What does all this mean for professional communicators?

Opportunities

- The chance to reach new and younger audiences.

- Simplifying complex policy or organisational messages by working with trusted online voices.

- Experimenting with new forms of storytelling that resonate outside traditional media formats.

Risks

- Loss of credibility if organisations rely on influencers known for partisanship or misinformation.

- The spread of unchecked narratives that undermine trust in institutions.

- Potential backlash from regulators, journalists, or the public if influencer engagement looks like propaganda rather than communication.

How Communicators Should Prepare

Some suggestions:

- Monitor the influencer landscape – know who the key players are in your sector and geography, and how they align politically.

- Develop ethical engagement frameworks – set clear criteria for who you will partner with, based on credibility, transparency, and alignment with values.

- Scenario planning – anticipate what happens if government or corporate leaders prefer influencers over independent journalists, and advise on the risks.

- Champion trust and accountability – communicators can lead by reinforcing the value of accurate, transparent communication, even in fragmented media environments.

A Turning Point

If the White House can seat TikTokers in its briefing room, who might be next at No.10, the Élysée, or the European Parliament?

This is more than a novelty. It’s a sign that the way political power communicates is changing. For communicators, the challenge is twofold: to understand how to work with this new class of media actors, and to ensure that in doing so we don’t erode the very trust and accountability that underpin our democracies.

The profession has an opportunity – and a responsibility – to shape how this plays out. The question is whether we are ready to step up.