In an increasingly volatile world, where power is too often wielded against the vulnerable, digital tools are becoming lifelines for those most at risk. A recent story from Rest of World has stayed with me, not only for what it revealed about the current situation in the United States, but also for what it made me reflect on closer to home.

The story highlights a growing ecosystem of mobile apps designed to help undocumented migrants in the US navigate the sweeping immigration enforcement actions, including deportation, now underway by the Trump administration.

These digital tools aren’t about convenience – they are, in many cases, about survival.

Apps on the Front Line

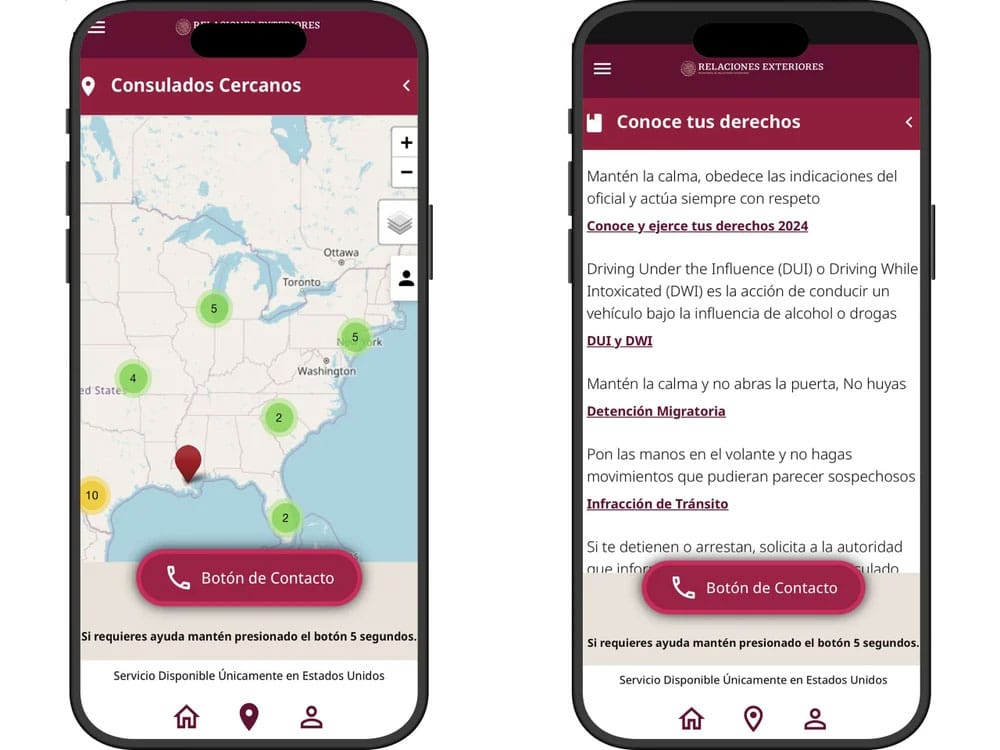

A good example is Hack Latino, an app that alerts users to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) patrols in real time. Or Know Your Rights 4 Immigrants, which reads your legal rights aloud in English for police officers, and in your chosen language for you.

Other apps, such as Mexico’s ConsulApp Contigo or Guatemala’s ConsulApp Guate, aim to help migrants in the US access consular services rapidly in emergencies.

Some operate like community watch systems of the 1990s, but upgraded for the smartphone era. Real-time warnings of immigration raids are shared through Facebook, WhatsApp, or Signal, and then logged in the respective apps. The tools are decentralised, grassroots, and deeply embedded in the daily experience of those at risk.

But the environment is changing fast – and not in the migrants’ favour. In some US states, new laws threaten to criminalise the act of assisting undocumented individuals.

One long-standing app, Notifica, was taken offline in February after its developers could no longer guarantee user security. Even well-established platforms like UK-based RefAid, which serves 41 countries, have scaled back US operations due to rising pressure.

A US-Specific Response – For Now

What’s especially striking about the rise of these migrant-focused apps is that they appear to be uniquely American in scope and urgency. The United States has harboured a large undocumented population for decades – the Migration Policy Institute estimated it at more than 11 million in 2023, with Pew Research and government figures ranging between 11–12 million.

Yet only now, under the renewed enforcement push of President Trump’s second term, has this long-standing issue triggered a technologically coordinated grassroots response.

In contrast, across the EU and in the UK, undocumented migration remains a serious political and humanitarian challenge, although not on the scale of the United States. Similar digital support systems appear to be absent, except for RefAid, which I mentioned earlier.

While NGOs in Europe do provide legal advice and support services, the idea of apps warning of immigration raids or enabling real-time consular coordination is far less visible, if it exists at all.

Part of the reason may lie in the nature of the migration issue itself.

In the US, the undocumented population includes millions of individuals who have lived and worked in the country for many years – families, neighbours, co-workers – who are now facing renewed deportation efforts. In the UK and across much of Europe, the challenge is more visibly focused on irregular border crossings – particularly in the UK, where small boat crossings from France have become a daily political flashpoint.

These differences matter: they shape the policy conversation, the tone of public debate, and the kinds of technological interventions that emerge in response. In the US, app-based tools are helping entrenched communities shield themselves from enforcement. In the UK, no comparable tools appear to exist, and it’s unclear whether any would be politically acceptable if they did.

A New Form of Digital Resistance

Such tools do not eliminate risk, but they raise the stakes for those who would abuse power in the shadows. They reflect a broader trend: ethical innovation under pressure. In the absence of effective institutional protections, communities are building their own defences – one alert, one download, one message at a time. For the citizens of some countries, their governments are providing support via apps.

They also force us to ask uncomfortable questions. If civil society in the US can turn to technology for protection, what’s stopping others from doing the same? And where are the equivalent tools here in the UK or across Europe?

As we consider the role of digital platforms in society, perhaps the real measure of a digital platform isn’t how many users it has, but who it serves and how well it protects them.