The so-called "special relationship" between the United Kingdom and the United States is often described in terms of shared history, common values, aligned interests – and, of course, a common language.

However, when it comes to the English language, that foundation is more complex than it seems. As the old saying (attributed to George Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde, or Winston Churchill, depending on who you ask) goes, we are "two nations divided by a common language."

This linguistic divide, while often a source of humour or mild confusion, is increasingly interesting in a world shaped by global media, international mobility, and digital communication.

As a YouGov article in early April illustrates, American English is having a growing influence on how people in the UK use, spell, pronounce, and understand English.

The YouGov View: A Language in Transition

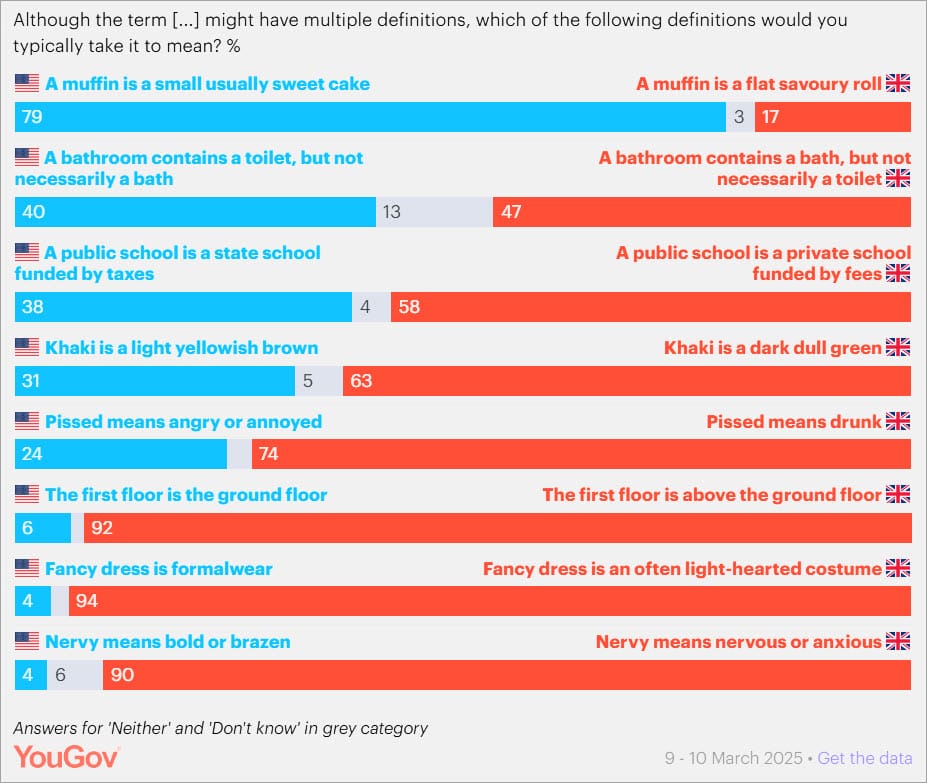

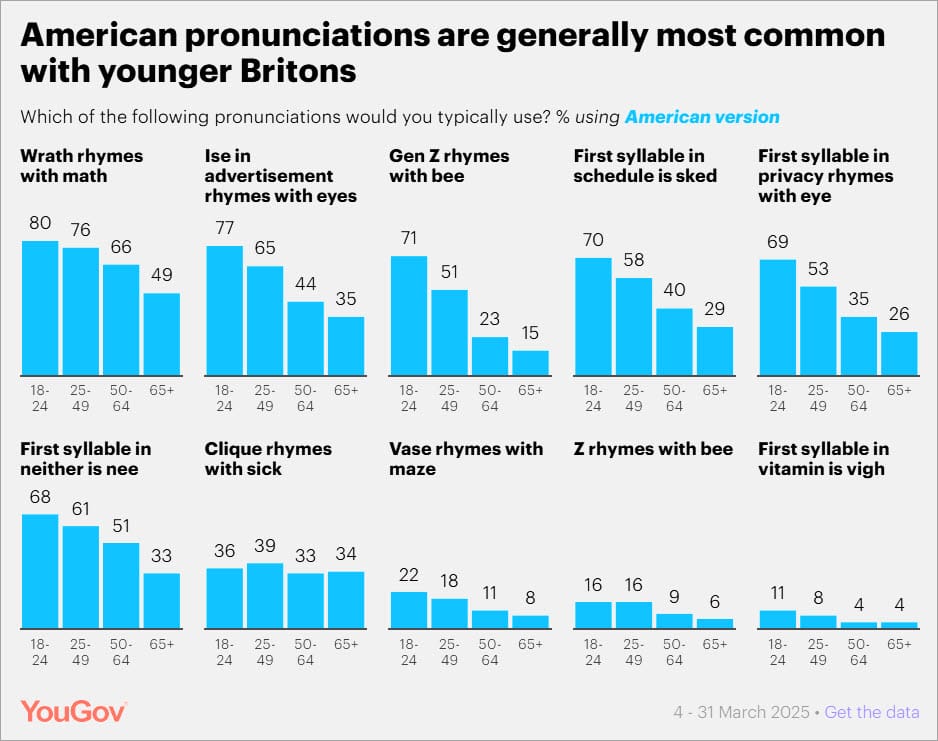

Research carried out by YouGov in March explores five broad areas where Americanisms have crept into British usage: vocabulary, definitions, spelling, pronunciation, and grammar.

The findings paint a picture of a language in flux, particularly among younger Britons.

- Vocabulary: American terms like landslide (preferred over the British landslip) and horny (favoured over randy) have gained wide traction.

- Definitions: 79% of Britons now associate the word muffin with the American-style sweet cake, not the traditional British flatbread.

- Spelling: American spellings are becoming more common, especially among the under-25s – airplane over aeroplane, for example.

- Pronunciation: The majority (68%) pronounce wrath to rhyme with math, American-style.

- Grammar: More than half of respondents said they’d use feeling good rather than feeling well.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, older generations still lean toward traditional British forms, while younger people are more flexible or unaware of the distinctions. Cultural influence – through entertainment, the Internet, and international business – plays a major role in this shift.

My Own Hybrid English

These findings prompted me to think about my own use of the language and how it’s been shaped by a life spent, to a great extent, outside the UK.

Though I still consider myself very much a British English speaker and writer, I’ve long noticed a kind of linguistic drift in how I express myself:

- I say zee, not zed, as in Gen Zee (Gen Zed just sounds weird to me).

- I pronounce schedule as skedule, not shedule.

- I write license (noun and verb) with an 's', even though the British noun is traditionally spelt licence.

- And yet, I firmly stick to British conventions like realise and organise, not realize or organize.

There’s no deliberate decision behind this mix; rather, it’s the result of years of exposure to different varieties of English – in conversations, media, and professional life – while living and working outside the UK and mixing in different multilingual cultures where a commonality is that everyone speaks and writes English of one flavour or another, in varying levels of fluency.

My language, like that of many others, reflects the world I’ve inhabited.

I've often thought that the British (frequently criticised by others for being so monolingual while the critics take the time to learn English as an additional language) might be onto something, so why bother learning any other language – soon, everyone will be speaking English, the thinking seems to go.

Of course, as a fluent speaker of Spanish as my second language, I hasten to distance myself from such thinking!

Toward a Global English?

This brings me to a broader, intriguing question: Are we moving towards a kind of homogenised, global English? A version of the language shaped not just by British or American usage, but by the growing number of people for whom English is a second (or third) language?

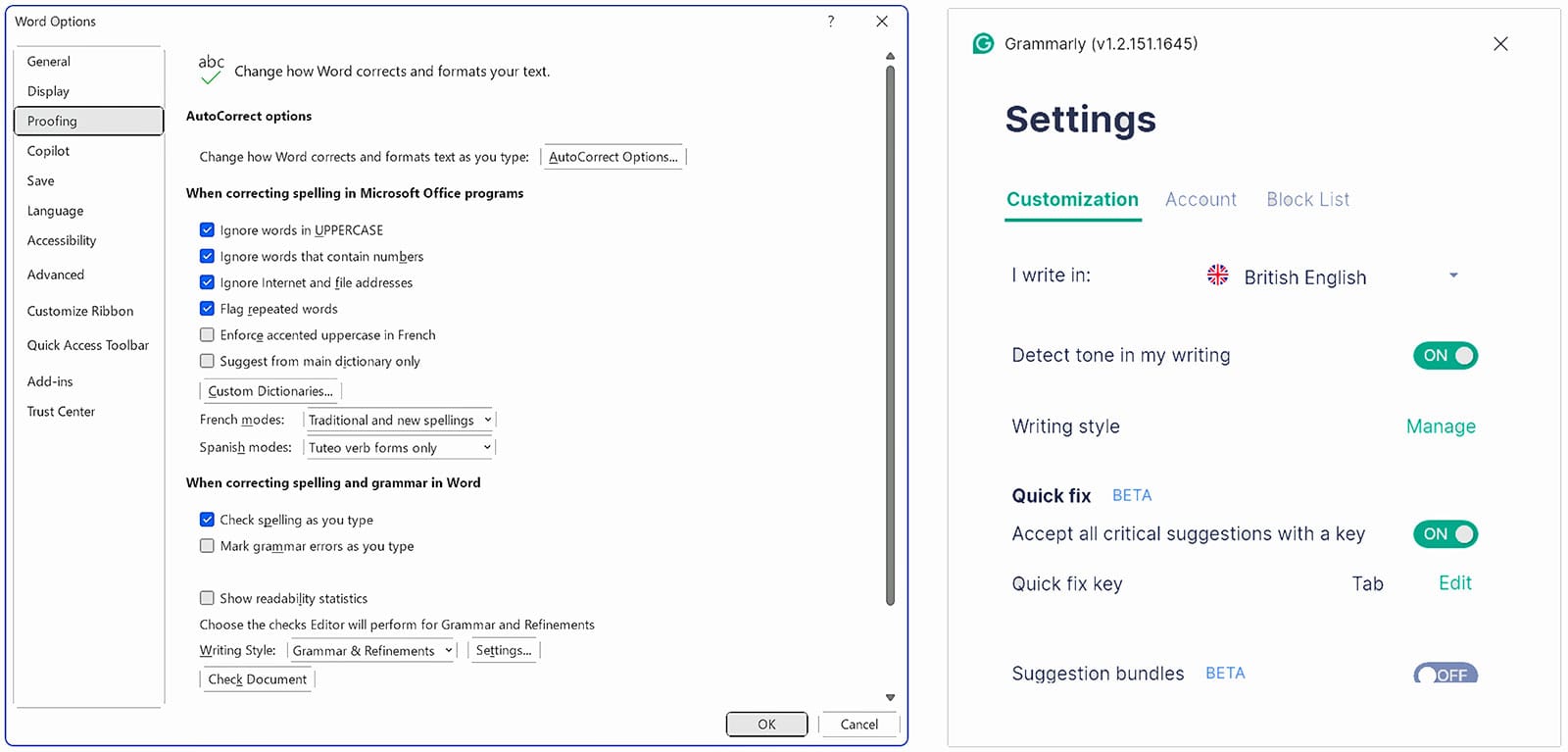

Not only that, but I see moving in a particular lingual direction prompted by spell checkers in the apps we use. It's not just Word – grammar aids like Grammarly work across countless apps, reinforcing these norms even more.

If you don't have the right English version set for spelling and grammar, you'll get prompted constantly with the squiggly red or blue line beneath words the checker sees as incorrectly spelled or grammatically dubious.

Indeed, grammar and spellcheck tools – not to mention autocorrect – often default to American English norms. Anyone who writes in British English will know the frustration of being told their spelling is “wrong” by their software that typically is set to American English.

I’ve yet to find comprehensive research tracking this shift, but there are early indicators. Scholars and commentators have started exploring what is sometimes called “International English” – a neutral, simplified, and practical version of the language that functions well in global business, online communities, and multinational teams.

A lingua franca, in other words. (Arguably, English already is the global lingua franca.)

If an internationally recognised version of English were to emerge – one that took account of global usage patterns and wasn’t tied to any one nation – it might make life easier for many. Fewer red squiggly lines. Fewer debates over -ise vs -ize. And perhaps a greater sense of linguistic belonging for non-native speakers.

As with much in today's society, our youngest generation holds the keys to what happens next.

Meanwhile, YouGov's complete analysis is well worth a read. Among the many other findings are gems like these:

- Some American spellings are even the norm among Britons, with around six in ten (58-61%) spelling fulfil with two ‘l’s and artefact with an ‘i’ rather than an ‘e’. Brits also seem to agree with Americans on dropping the a from words historically spelled with an æ, with 65% spelling it ‘encyclopedia’ instead of ‘encyclopaedia’.

- The inconsistent ways in which American English is catching on can also be seen when it comes to grammatical differences. While half of Britons (51%) would – perhaps controversially – describe themselves as ‘feeling good’, compared to 34% who say they are ‘feeling well’, just 8% would say ‘can I get a cup of tea’ rather than ‘can I have a cup of tea’.

- Britons still largely favour the British convention of putting the day first when writing out the date in full, with 85% favouring the style of ‘1st January’ or ‘1 January’, while just one in eight (12%) prefer the more American routes of ‘January 1st’ or ‘January 1’.

Language is a living thing, constantly shaped by the people who use it. As English continues to evolve – in Britain, America, and far beyond – we’ll likely see more blending, more adaptation, and perhaps, a new kind of consensus about what “correct” usage looks like.

For me, this isn’t something to lament. It’s a reminder that language reflects life – and life, increasingly, is global.